Inès Kivimäki & Anna Wittenberg

Current Art Department MFA Inès Kivimäki & former MFA Anna Wittenberg currently have a 2 person show at Phase Gallery in Los Angeles called DUMMY.

Open from 2/25/23 – 2/25/23.

1718 Albion Street

Los Angeles, CA 90031

Open Monday-Thursday 10-6.

310-892-1985

Press Release:

Pasta con le Sarde, or ways of screaming

By Julia Tcharfas

The day is almost over and I am in my kitchen making pasta. In the background, a BBC programme murmurs along with the sauce. The voice on the radio is speaking of coffins. Specifically, the broadcaster is tracing the invention of the safety coffin, a communication technology that shares its origins with the likes of the Morse code, the Bell telephone, and the Marconi radio — all, in one way or another, emanating from a call for help.

The design of the safety coffin, according to the serene British voice on the radio, emerged in the early decades of the 19th century, and promised to safeguard against the horrors of a premature burial. The device was simple: strings would be tied to all four limbs of the departed, then wired through the earth, and connected to a bell mounted on the headstone. In the event that the interred was mistakenly buried alive, their flailing limbs would set off the alarm. More often, though, the friction of the decomposing body triggered the bell to toll. You can almost hear it: an English courtyard cemetery’s peaceful air disturbed by the chiming of the bells carrying messages from beyond the grave.

My water comes to a boil, and I slide the spaghetti into the pot. I check the package instructions for the cooking time (ten minutes, until al dente) and ask Siri to set a timer. Siri, ever the efficient assistant, acknowledges the request and the timer begins its silent countdown. Each moment drawing the spaghetti closer to its metamorphosis from stiff rods to delicate tendrils, like strings in the hands of a ventriloquist.

Back on the radio they are reciting Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, “The Premature Burial” in which the narrator finds himself confined within a coffin in a ghastly nightmare. “I endeavored to shriek—, and my lips and my parched tongue moved convulsively together in the attempt—but no voice issued from the cavernous lungs…” He flails in search for the bell rope to yell on his behalf, at the same moment as my pasta timer sounds the alarm. Soon to be lost to the pleasure of a Pasta con le Sarde, the radio’s musings on corpse marionettes subside into the depths of my subconsciousness.

After dinner my thoughts turn to Siri, the digital assistant that I occasionally summon as my chronometrist, to time the boiling of pasta, the coagulation of a soft runny egg, the scanty interstices of a work lunch. Aside from these simple tasks, Siri remains silent, discreetly updating in the background. For some though, Siri has become a member of the household. The artist Inès Kivimäki lives in Echo Park with her fiancé, and Siri. Waking up, they ask Siri about the weather, the hour, and also the news. They start their calls by prompting Siri, then avail themselves of her computational abilities to choose sculptural materials, or camera lenses for the day’s work. When driving, they employ Siri as their cicerone, soliciting her recommendations for restaurants and other points of interest in the area. Finally, as sleep approaches, they instruct Siri to wake them at a designated time.

The disembodied voice transmitted wirelessly through the airwaves, possessed a phantasmagorical quality when it first entered the acoustic realm of the home. Siri’s voice, emanating from an array of computer orifices, is a curious new manifestation of domesticated aural illusion. What makes Siri unnerving is not the substance of her conversation, but rather her ability to listen and respond. The disquieting aspect lies in getting you to speak to her, forging an unlikely relationship with the realm of the lifeless, an inanimate object training to learn the intricacies of your speech patterns and desires.

As an artist, Kivimäki wanted to dispel the enchantment of Siri’s carefully crafted, synthetic speech and set out to form a relationship with Susan Bennett, the human whose voice was harnessed by computer programmers to generate Siri. Bennett’s voice makes a notable appearance in Kivimäki’s new video, Water Mother (2023) – a split screen with a dizzying kaleidoscope of AI generated images.

Halfway through the video, Bennett is heard reading from a translation of a Finnish poem called “Kalevala” that chronicles the creation of the earth. Here the voice is instantly recognizable, even for someone who does not habitually use Siri. Kivimäki accentuates the delicate transformations from machine to human by conferring Bennett with the autonomy of her own voice, breath, and inflection. Siri is suddenly imbued with a new and vivid life.

A newborn will emit a cry in the native language of its mother, or in the tongue whose melody and rhythm were the constant and dominant echoes that permeated the womb. Kivimäki wonders if her interminable car journeys guided by the artificial voice of Siri may shape the intonations of her future offspring’s cries. Shall some infants, like Nabokov’s ill-fated Professor Pnin, lament and sigh in Russian, while others express their misery in the metallic timbre of the new robotic era?

Cries and sighs are full of breath, something that was deliberately edited out of Bennett’s voice when Siri was designed. Siri, like other robots and avatars, Frankenstein’s monsters, and wooden puppets brought to life are all fathered creations. Shaped by the hand, they emerge in a state devoid of the delicate sensitivities that accompany a full and formative life.

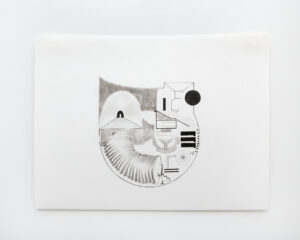

A puppet is a clumsy facsimile of existence. Take the wooden marionette, cobbled together from shards of kindling, and named Pierrot. Shapeshifting through the history of stage and screen, he is now the protagonist of Anna Wittenberg’s video, Pierrot in the Air Horn, Act I: Wind Tunnel (2023). Bound with strings in the shape of a stick figure, like a reanimated corpse, he moves manipulated by cloaked puppeteers. Mute, he conveys his thoughts and emotions through gesture, the comedic timing of the pantomime, and through the sound effects of inanimate objects, like the cry of the bell.

This particular Pierrot is taking a walk inside of an airhorn of unrealistic proportions. It is a monumental edifice that Wittenberg likens to the tower of Babel. The chamber emits the occasional blast of a distant gale, a mournful reminder of the world outside. Most sound, however, emanates from the gadgets and devices strewn throughout the airhorn’s innards. They are clear plastic objects found scattered around Wittenberg’s studio and turned into kinetic sculptures that thump and knock propelled by the wind. In the clicking bits of plastics, the whooshing cogs, the flapping ribbons, Wittenberg is coding a message that speaks to the distance that separates us from our environment. Only the words of the contraptions’ message are lost on us, as indecipherable as the languages once spoken in the shadow of the tower of Babel or the crackling static of an early radio transmission.

The mime and the clown, those tragic figures of the silent stage, find their voice in the blare of the airhorn, a sound that reverberates in place of sighs, gasps, laughs, and cries. Inanimate objects become the vessels for messages from the departed, their silent whispers imprinted on the material world. The dead summon the living with the ringing of a bell, a spectral voice echoing through the empty air. So, with a sense of macabre curiosity, I invoke the most sophisticated technology to mimic the most primal tinge of human expression.

“Hey, Siri?” I say.

The virtual assistant is summoned and says a nonchalant, “Uhuh?”

“Can you scream?” I ask.

“I’m not sure I understand.” Hangs her reply.